On January 19, a process that has been 80 years in the making will get underway at United Nations headquarters in New York. Member states will begin preparation mandated by the General Assembly to create an international treaty to prevent and punish crimes against humanity.

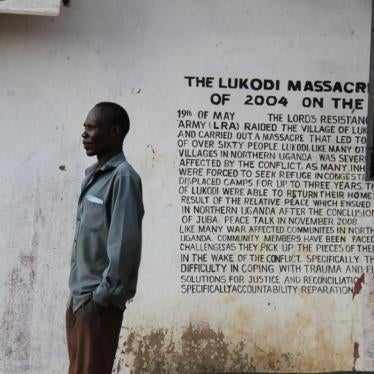

Crimes against humanity are acts of extermination, torture, enslavement, rape, forced pregnancy, persecution, enforced disappearance, and apartheid, among others, when committed as a part of a widespread or systematic attack directed against a civilian population. They are among the gravest offenses under international law. Despite their seriousness, crimes against humanity have never been specifically codified in an international treaty to prevent and punish these acts. Since there is no treaty, many countries have no legislation that they can use to prosecute people for these crimes.

The official start of this multilateral effort, a significant marker on a long road, comes with high stakes and entrenched opposition at a difficult time on the international terrain. From Washington to Moscow, power is increasingly treated as a substitute for legality. Many governments have openly defied the laws of war and abandoned their commitment to human rights and the rule-of-law as civilians pay an ever-rising price.

In this world of escalating risk, a treaty to address crimes against humanity could decisively expand protections for civilians and reaffirm the relevance of international law and multilateralism.

But to be meaningful, the convention cannot simply fill a legal lacuna with text. It must, in practical ways, increase protections for civilians at risk by creating an effective and victim-accessible instrument consistent with international human rights standards. States that join the convention and make it part of their domestic law will be obligated to try or extradite suspects before their national courts. This will dramatically expand avenues for accountability and redress for survivors of crimes that are among the worst imaginable.

History

Underscoring its importance, the backstory of this process dates back to the post-World War II quest for accountability for the crimes committed by Germany’s Third Reich. At the Nuremberg Tribunal, prosecutors brought charges for crimes against humanity alongside war crimes and crimes against peace. The judges convicted several leaders of these offenses. The newly formed UN General Assembly affirmed the concept when it adopted the Nuremberg Principles.

But in the period when the Geneva Conventions for war crimes (1949) and the Genocide Convention (1951) were completed, there was no effort to create a crimes against humanity treaty. As the decades passed, this had a stark impact on civilians in all regions of the world.

The concept regained momentum in the 1990s through the statutes and jurisprudence of the ad hoc tribunals for the former Yugoslavia and Rwanda, as well as the Special Court for Sierra Leone. Building on this case law, the 1998 Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court included a detailed definition of crimes against humanity that is now binding on 122 ICC member states.

A major step forward came in 2019, when the UN’s International Law Commission transmitted its Draft Articles on Crimes against Humanity to the UN General Assembly’s legal committee—the Sixth Committee—recommending the negotiation of a treaty. Finally, after years of delay and sustained obstruction by a small group of countries led by Russia, the General Assembly, by consensus, agreed in 2023 to convene negotiations on a convention.

The Schedule

The process will unfold over the next three years. The January 2026 Preparatory Committee meeting is intended to help states formulate amendments to the draft articles. It will also confront a fault line that has already emerged in earlier debates: whether civil society organizations without accreditation from the UN’s Economic and Social Council will be permitted to participate in the process.

April 30, 2026, is the deadline for states to submit amendments for inclusion in a “compiled text” that will be forwarded to the negotiating conference as the starting text to consider. A second, four-day Preparatory Committee meeting in 2027 will focus on procedural rules for the negotiations and on the selection of the conference’s leadership.

The negotiations will take place in two three-week sessions in 2028 and 2029. Their outcome will determine whether the international community will finally close one of the most glaring gaps in the international legal system or allow the resistance of a handful of countries to derail the treaty.

Aligning the Forces

Countries have coalesced into various blocs around this treaty.

The largest group—a loosely organized but broadly aligned cross-regional coalition of approximately 100 states—actively supports completing the treaty. Led by Mexico and The Gambia, in 2024, these states co-sponsored General Assembly Resolution 79/122, which set the schedule for the conference and signaled a serious intention to complete an effective treaty.

Arrayed against this effort is a much smaller but determined group, including China, Russia, Iran, Cuba, North Korea, and Eritrea. Even though this treaty is 80 years overdue, these countries claim that working on a new convention is premature. They do not see the need for a treaty and contend that the Draft Articles should be returned to the General Assembly’s legal committee for further study and revision. During negotiations on Resolution 79/122 to create the process, Russia succeeded in delaying the timeline by employing a familiar repertoire of threats.

Between these two poles sits a sizable group of states. Some have expressed mild support for moving toward the proposed treaty. These states need to be more convinced of the imperative for this treaty and that proposals to amend the Draft Artiles will strengthen the impact of the convention.

Others have yet to articulate a clear position, including the United States under the Trump administration. At the Sixth Committee session last October, the US representative said that Washington is “still considering our specific views,” leaving open the question of whether the Trump administration will ultimately bolster the negotiations, seek to reshape them, block progress, or stand aside at a critical juncture.

Approach to Strengthen and Defend the Text

January’s session creates a clear imperative: to advance ambitious, well-considered amendments that strengthen the Draft Articles, while simultaneously defending core operational provisions essential to enforcing the treaty.

Over the last three years, debate and attention have focused on whether to expand the list of acts constituting crimes against humanity. Proposed additions have included slave trade, gender apartheid, forced marriage, and specific crimes against children. Other potential offenses—such as colonialism, starving civilians, and severe environmental harm—have also attracted interest from some states. Advocates are also pushing for the Convention to explicitly recognize crimes committed against people with disabilities, a group historically excluded from international legal frameworks, yet who have faced specific atrocities. More than 80 countries have signaled openness to considering a limited number of targeted additions.

At the same time, the International Law Commission’s draft articles provide a solid foundation on which to negotiate a final treaty text. It is critical to preserve key provisions that give the convention operational force. These include maintaining the current approach to command responsibility under Article 6, to the duty to cooperate in preventing crimes against humanity under Article 4, and to jurisdiction under Article 7, which enumerates—without a hierarchy—the bases on which states could prosecute or extradite suspects.

Weakening operational provisions such as these would hollow out the convention regardless of how many additional crimes are added to the list of crimes against humanity.

The Importance of Wide Civil Society Participation

Increasingly at the UN, the issue of civil society participation in multilateral negotiations has become a flash point. The January Preparatory Committee’s decision on civil society participation by groups lacking affiliation with the Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) will be an early test of the relative strength of the contesting groups of states mentioned above.

Civil society observers—academics, lawyers, activists, survivor groups, and nongovernmental groups large and small—are indispensable to enriching the substance of the negotiations. Activists and victims ground the debates in the realities of how crimes against humanity are committed, documented, and experienced by the communities most affected by the crimes. Academics bring decades of legal expertise, and practitioners assist states in ensuring that provisions are workable, enforceable, and responsive to contemporary patterns of crimes against humanity.

In addition, civil society will be the key force in ensuring that the significance of these negotiations resonates far beyond the UN conference room in New York. As international law is increasingly portrayed as remote, technical or hollow, civil society actors are often the ones capable of mobilizing public engagement and sustained attention. A process closed to civil society would confirm, rather than counter, the perception that international law operates removed from reality.

The obstructive group of states can be expected to work systematically to weaken these and other essential provisions.

This is the first international criminal law codification effort under UN auspices since the 1998 adoption of the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, and international criminal law has certainly evolved over the last nearly 30 years. If the Convention is to remain relevant through the twenty-first century, it must reflect developments in international law and be capable of addressing contemporary forms of mass harm.

Compromise will be inevitable and states will rightly require provisions that allow some flexibility in turning the treaty text into national law. However, limiting amendment proposals to what might be acceptable to nearly all UN member states in advance of actual negotiations risks pointless concessions and irreparably weakening the text.

Anyone who has paid even minimal attention to recent processes at the UN knows that nothing is “universally” agreed to. In the current geopolitical climate, “universality” as a guiding objective can become a rationale for retreat rather than a pathway to an effective convention.

Against this backdrop, a cautious approach by supportive states carries real risks. An overly restrictive posture—particularly one driven by a desire to neutralize opposition or secure “universal” buy-in—would amount to self-censorship before negotiations even begin.

The upcoming Prep Com should set the political and substantive trajectory of the treaty. It should affirm openness and legitimacy by deciding that non-ECOSOC civil society observers can participate in the conference, and it should create conditions that encourage states to advance concrete amendments to strengthen the Draft Articles. The session should be marked by active, cross-regional engagement and substantive debate on proposed amendments. Above all, governments should resist the pull of premature minimalism, which would only entrench obstruction and sap momentum at precisely the moment when ambition is required.