- The Hungarian government is failing to ensure older people’s rights to social security and an adequate standard of living, including access to sufficient food, medicine, and energy.

- The rise in poverty among older people, which became evident during sharp inflation in 2022 and 2023, highlights longstanding structural problems with the Hungarian pension and social security system.

- Hungary should raise the lowest pensions to reduce pension inequality and guarantee the rights of all older people in the country to social security and to an adequate standard of living.

(Brussels, January 14, 2026) – The Hungarian government is failing to ensure older people’s rights to social security and to an adequate standard of living, including access to sufficient food, medicine, and energy, Human Rights Watch said today. The authorities should urgently review retirement pensions and take immediate steps to increase pension levels in line with human rights obligations to address rising poverty among older people.

“The Hungarian government expects hundreds of thousands of older people to survive on low pensions that are evidently inadequate,” said Kartik Raj, senior Europe researcher at Human Rights Watch. “Hungary’s insufficient social security system forces many older people to choose whether to spend their meager pensions on food, medicine, or heating, and which essential item to do without.”

Official data show that about 2 million people received age-related pensions at the end of 2024, more than two-thirds of them below the monthly gross minimum wage (266,800 HUF, or €676). Almost a quarter of all pensioners (471,000 people) receive pensions below the official income poverty threshold (173,990 HUF, or €441). Higher numbers and proportions of women receive pensions below these thresholds.

Human Rights Watch interviewed 45 people ages 65 to 91 who receive age-based contributory pensions in Budapest and two rural communities, and social policy experts and pensioner associations, and analyzed official data.

Hungarian Central Statistical Office data show a rapidly rising risk of poverty for older people. The at-risk-of-poverty rate for people 65 and over increased from 6.3 percent in 2018 to 16.1 percent in 2023. Nearly one-in-five older women is at risk of poverty. The data show a general decline in the at-risk-of-poverty rate across the population and for people under 64; which the authorities have chosen to emphasize while downplaying rising poverty for older people.

The increase in poverty experienced by older people coincides with rising inflation since 2018, which skyrocketed in 2022 and 2023 when food price increases in Hungary outstripped those in other European Union countries. Older people on low pensions were among those hardest hit, with many unable to maintain adequate diets due to the surging prices of staples, such as sugar, oil, flour, dairy, meat, and fruit.

Hungarian authorities responded by managing gas prices, and imposing partial price controls on key food items in 2023 and 2025. However, vendors increased prices of other uncapped goods to make up their losses, limiting the effectiveness of price capping.

The plight of older people in Hungary is at odds with the government’s repeated claims that it prioritizes the wellbeing of “ordinary Hungarians,” Human Rights Watch said. These claims also come amid international concern over Hungary’s anti-democratic rule and widespread violations of liberties and freedoms.

The rise in poverty among older people highlights longstanding structural problems with the Hungarian pension and social security system. These include a flawed pension indexation method that causes low pensions to lose value faster than higher ones, perpetuating inequality, and leaving those with the lowest incomes furthest behind.

“People who have millions can’t imagine this life, when you have nothing to spend and are just surviving,” said a 90-year-old woman who worked in a state-owned textile company and then ran a state shop in Jász-Nagykun-Szolnok county, until she retired in 1991. “A person who worked for 40 years shouldn’t have to live like this. We need a more equal pension system.”

Government steps to provide additional financial support to pensioners have only provided partial relief and have not addressed structural inequalities. In 2020, the government gradually introduced a “13th month pension,” providing all pensioners with an extra monthly payment per year since 2024. In November 2025, the government proposed creating a “14th month pension.” Although older people interviewed appreciated the additional support, many want the government to address the fundamental problem that their monthly pensions are too low to reverse the increasing at-risk-of-poverty rate among older people.

In July 2025, the government decided to issue one-off 30,000 HUF (€76) in food vouchers to all pension recipients, redeemable for “cold food” between October and December. Many older people interviewed said having the cash equivalent added to their pension, instead of vouchers, would have allowed them greater independence over how to spend the funds. A few dismissed the meal vouchers as a political gimmick and others said they were worth significantly less than a tax refund for pension recipients that was initially proposed by the government, but abandoned due to administrative complexity.

Hungary has an obligation under the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights to ensure all economic, social, and cultural rights, including the rights to social security, to an adequate standard of living, and the highest attainable standard of health. International human rights standards, treaties, and related guidance on social security set out clear requirements for the adequacy of social security benefits. European social rights law provides protection from poverty and social exclusion, as well as a specific “right of elderly persons to social protection.”

Hungary should urgently review the adequacy of pension levels, raising the lowest pensions to reduce pension inequality, to guarantee the rights of all older people in the country to social security and an adequate standard of living. In particular, the government should take immediate steps to ensure that no one is left without adequate nutritious food, sufficient energy to warm their home, and necessary medication and supplies to ensure their health.

“Food coupons or a hastily legislated extra month’s pension are band-aids to address Hungary’s open wound of rising pensioner poverty,” Raj said. “If the Hungarian government genuinely cares about older people’s right to social security, it should urgently increase low pensions, take decisive steps to make the system more equitable, and ensure that all older people in the country can afford a decent, dignified living standard.”

For further data analysis and detailed accounts by the people interviewed, please see below.

Methodology

In October and November 2025, Human Rights Watch interviewed 45 people—29 women and 16 men—between ages 65 and 91, receiving low pension incomes from the public contributory pension in Budapest and rural communities in Szabolcs-Szatmár-Bereg and Jász-Nagykun-Szolnok counties. Most received pensions less than 173,990 HUF/month (€441), the at-risk-of-poverty threshold, in line with the EU definition of 60 percent of median equivalized net income in a given country.

Real names are used where interviewees granted consent; pseudonyms are used for those who requested anonymity. Human Rights Watch informed people interviewed of the purpose and voluntary nature of the interview and obtained verbal consent. Nobody received compensation for providing information.

Human Rights Watch also interviewed experts on social policy, pensions, and poverty, as well as representatives of pensioner associations.

Human Rights Watch analyzed official data from the Hungarian Central Statistical Office, Eurostat, and data from social scientists and municipal authorities including time-series data on poverty rates, pension levels, and inflation, and compared income distributions across age groups. The research accounts for the fact that Hungary has two types of minimum wage: a “gross minimum wage” for positions that require no formal educational qualifications, and the “guaranteed minimum salary” for positions that require evidence of completing high school.

Summarized findings and additional questions were sent to the Hungarian government prior to publication. No response was received.

To assess the adequacy of pension levels, Human Rights Watch applied international human rights standards, including the requirements under the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights that social security benefits must be sufficient to enable recipients to enjoy an adequate standard of living. Human Rights Watch reviewed multiple indicators of adequacy, including poverty thresholds, the relationship between pensions and statutory minimum wages, inflation and food price trends, and the real value of pensions over time. Human Rights Watch compared relevant benchmarks with official pension distributions to evaluate whether current benefit levels ensure income security for older people.

The research uses a Euro-Hungarian Forint conversion figure of €1 = 395.44 HUF, based on the European Central Bank’s average exchange rate. The rate derives from the average across 2024, to ensure consistency with other data drawn from 2024. Euro figures are rounded.

Key Pension System Features

Hungary’s pension system is based on a compulsory social insurance scheme financed primarily through contributions from current workers, with additional funding from general revenue.

Old-age pensions are available to people who reach the statutory retirement age, currently 65, or those who have accumulated a sufficient number of contributory years. Women can, in some cases, retire after 40 years of eligibility (including employment and certain child-raising years) regardless of age, based on current legislation. Benefit levels are calculated using a formula that accounts for an individual’s lifetime earnings and contribution history, meaning people with lower wages or interrupted employment receive substantially lower pensions.

In the current system, pension eligibility generally requires at least 20 years of contributions, and a minimum of 15 years for the lowest tier of benefits. People with fewer years are excluded from the system, but those who do not qualify can apply for a ”minimum pension” of 28,500 HUF/month (€72). Pension experts consulted said that very few people receive the minimum pension.

Groups most affected by low pension incomes include women with interrupted employment due to unpaid care responsibilities and people who worked in informal or partially informal jobs, raising concerns about structural discrimination and the state’s obligation to ensure universal and adequate social security to all older people.

Hungary’s Fidesz government abolished the country’s mixed public–private pension system in 2011, nationalizing the system into a single public pillar, using legislative means to override property rights and legal certainty. The post-2010 system has over time exacerbated income inequality between pensioners.

Structural Problems with Pensions and Falling Living Standards

The experience of older people on fixed pension incomes, which came into stark relief during the cost-of-living crisis of 2022 and 2023, highlighted at least four structural problems with the Hungarian pension and social security system.

First, it is a “pure pay-as-you-go state pension system,” with benefits calculated based on years of qualifying work and wage-based contributions during those years. People who had comparatively low earnings during Communist rule, or in the post-Communist transition, and retired in the 1990s or early 2000s generally tend to receive lower pensions than people who have more recently become eligible.

Second, it was commonplace to earn unreported income in the informal economy in the latter decades of Communist rule, and successive governments continued to allow “off the books” employment after the transition. As a result, many people discover when they retire that their pensions are much smaller than they expected.

Third, between 2009 and 2011, Hungarian authorities stopped factoring in wages into annual pension increases, (as used to happen under the so-called Swiss indexation mechanism, which indexed pensions half by inflation and half by nominal wage growth), choosing to base subsequent annual increases solely on the consumer price index. Given rapid wage increases in the late 2010s, pensions have not kept up with wages and the cost of living. Some pension experts and pensioner advocacy groups argue that reintroducing the “Swiss indexation” mechanism would help address pension inadequacy problems. The indexed increases also often lag by several months, which causes particular problems for pensioners receiving low incomes during rapid inflation.

Finally, the data also bear out a wider demographic trend that older women tend to live longer than older men, and given that women in general receive lower pensions, higher numbers and proportions of women receive low pension incomes as they age. Nearly a quarter of all people receiving an old age pension are women over the age of 75. Human Rights Watch estimates that the median man receives an old age pension that is 16 percent higher than that received by the median woman. Nineteen percent of older women are more likely to be at-risk-of-poverty, compared with 12 percent of older men.

Case Study of One Municipality

Local authorities in one of the municipalities that Human Rights Watch visited provided information on the ages of all residents receiving pensions and gross monthly pension payment amounts. At the time of the visit, 98 pensioners between ages 63 and 92 received age-related retirement pensions. All but nine received pensions below the poverty threshold, and all received pensions lower than the gross monthly minimum wage.

Older People’s Concerns Over Lack of Pension Equity

Older people raised concerns about their pension incomes not meeting living costs, their perception that they were being treated unfairly, and the inequality embedded in the Hungarian pension system. Many said they depended on free or subsidized meals from municipal social services, and in some instances through charities. Although municipal provision of free or subsidized meals do form part of the state’s efforts to guarantee the rights to social security and to an adequate standard of living, and most likely help address food insecurity among older people, Human Rights Watch noted that such provision varied significantly between municipalities and may not provide uniform or comparable coverage to all older people on low incomes across the country.

Béla, 87, raised animals in a state-run agricultural cooperative in a village in Szabolcs-Szatmár-Bereg county until it ceased to exist in the early 1990s. He was then unemployed until he reached pension eligibility age. His pension is 148,665 HUF/month (€376), which he calculates leaves him with about 10,000 HUF (€25) as his monthly disposable income after paying for food, utilities, medicine, and home maintenance. Béla said:

I get a lunch service delivered by the municipality. I spend what I have on breakfast and dinner. I always pay my bills. It’s not fair. I don’t even get half of what I should for the work I did. All the people who had jobs like mine, who are still living, have very low pensions. If I could change things, I would … make sure that older people with less money can continue to live in villages, otherwise the villages will cease to exist.

“Zsuzsa,” 85, was born into a farming family in Jász-Nagykun-Szolnok county. The family’s land and tools were collectivized in 1959, after which she worked briefly in a state-run agricultural cooperative, and then left paid work to raise a child with disabilities. She resumed paid work at 38, in the state radiator factory, and was forced into retirement at 55, when state assets were sold off in the mid-1990s. She lives alone, and her pension is 138,000 HUF/month (€349). Zsuzsa said:

Those with high pensions say they worked hard and deserve it. No one worked harder than farmers and factory workers, but we are left on the periphery. There are hundreds of thousands of pensioners with very low monthly income. There has to be a fairer way to share the pensions. For example if everyone gets a 1.6 percent pension raise, for me it’s 2,000 HUF (€5), but for someone else who already has a high pension, it could be tens of thousands. I don’t want to say we should take pensions away from others, but we should make it fairer.

Tihomir, 78, was a cinema engineer in Romania, which he fled in 1989 living briefly in Germany, and then worked for more than 20 years in sales at an import market in Budapest. He said he had a good salary in his years working in Budapest, but realized when he began to claim his pension that he had not been in full legal employment during those years, and that due to contractual irregularities had not made the necessary social security contributions.

His monthly pension, including pension income from Romania, was 125,000 HUF (€316). Tihomir lives in affordable housing in Budapest and gets free meals from social services in his district. Tihomir said:

Without free lunch and my low-rent apartment, I could not survive. I am grateful to the local municipality. With the rising prices of medicines and groceries, I can’t afford healthy food anymore. I can’t buy fruit, the only fruit I eat is in the small cups of yogurt that cost 80 HUF (20 cents). I can’t afford even a soft drink. It’s sad the place I’m in now.

Erika, 83, and Anna, 80, are sisters who live together in an apartment in Budapest’s VIII district. Erika was a kindergarten educator and administrator until she retired in 2000, and Anna was a gymnastics teacher until her retirement in 2004 and had been an Olympic gymnastics coach. Following the most recent indexed increase, one of their pensions has increased to the point that it took them above the “at-risk-of-poverty” threshold and close to the “gross minimum wage” for two adults; their household income is 518,000 HUF/month (€1,312). Anna and Erika said that supermarket leaflets containing discount coupons had become “like a Bible” to them, as they now base their shopping almost solely on discounted products. Anna said:

We are not whining or complaining. There are people in worse conditions, of course. But we feel the hardship. If the government wants to build a future with long-term prospects, they should have more respect for the work previous generations have done. We worked, we had honest jobs, we built this country, we didn’t steal money, and now we can’t afford to live.

Choosing Between Food and Heat

Following the rapid inflation of 2022 and 2023, most of the older people interviewed reported either reducing their food intake, cutting back on heating their homes, or both.

“Anita,” 78, lives in a village in Szabolcs-Szatmár-Bereg county. She worked on farms and in a factory, and then in the post office from 1983 until her retirement. She spent some years receiving a disability benefit following an injury. Her retirement pension is 150,425 HUF/month (€381). Anita said:

I never miss buying medicine, but I cut back on other things like food or heating. I only buy what is needed. I like fruit, but I don’t buy it anymore. I make do with plums from my garden, and apples from my cousin. I raise my own chickens in the summer, freeze them whole, and cook them. If I cook, I make a dish that lasts for four or five days, and I’ve stopped eating lunch so the food lasts longer. I would eat more fish if I could, but I can only dream. The cost of firewood has gone up too.… And I need to pay someone to come and chop it. I only use the wood oven in the main room when I’m alone. I can’t afford the gas heating, but I need to keep it working for when the grandchildren visit.

Piroska, 91, lives in a town in Jász-Nagykun-Szolnok county. She worked in agriculture from when she left school in 1945, at age 11, until she retired in 1998, the year her husband died. She had received a letter notifying her of a raise shortly before being interviewed; she said her pension after the raise was just under 200,000 HUF/month (€505). To save money, Piroska switches on the heat only in the afternoon or spends the day at a center for older people.

Access to adequate food goes beyond mere subsistence, and can affect social participation and levels of social isolation. Older people reported no longer being able to afford “treats” like going out for coffee or a soft drink, as a way of spending time with friends. Many older women referred to rising fruit and vegetable prices affecting their ability to enjoy one of their favorite activities: creating preserves, jams, and pickles during the summer, for additional nutrition during the rest of the year and as an affordable way to give gifts.

“Kati,” 71, a retired teacher living in Budapest’s XI district, receives a pension of 175,675 HUF/month (€444). Reflecting on recent sharp food price increases, Kati said:

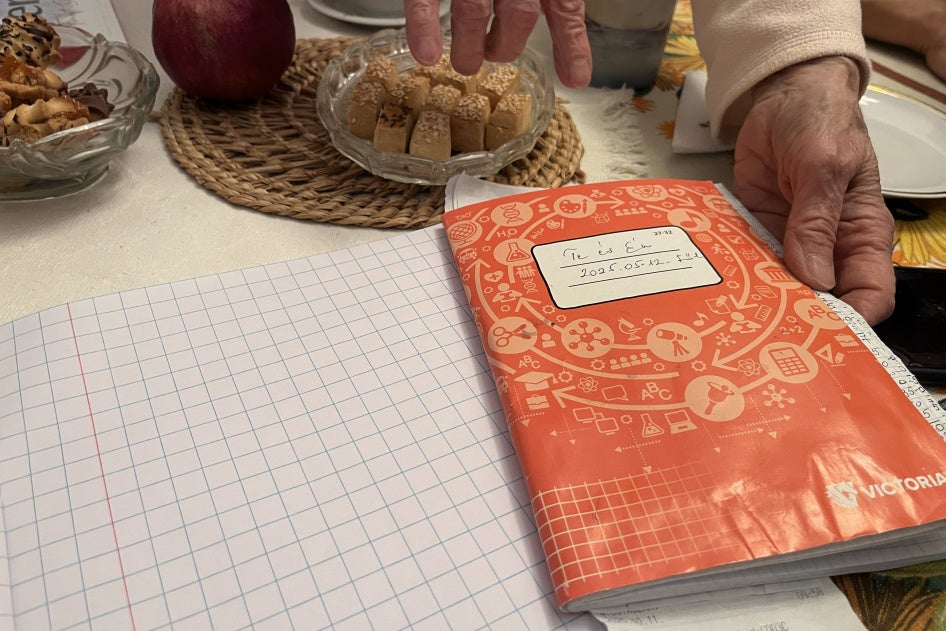

I always preserved fruit to make jam or compote for the whole family, but I can’t afford to do it anymore. I used to eat plain yogurt with my homemade fruit jam in the winter. I can’t have that anymore. That was always a gift I could make for others, even if I didn’t have a lot of money. I could make zakuska [a vegetable spread] and give jars to my friends, family, my language teachers. It was cheaper than buying chocolate, and also it’s homemade and shows care. I’m so sad I can’t do that anymore.

Difficulty Paying for Medication

Other older people said they cannot pay for medical supplies and prescribed medication to treat chronic health conditions, including diabetes, hypertension, asthma, and vascular disease.

Ildikó, 69, was a hairdresser for 43 years in Budapest, until she retired in 2017. Ildikó receives a pension of 77,000 HUF/month (€195), and blames this in part on the common practice in hairdressing of irregular pay arrangements leading to low contribution to social security, symptomatic of a wider informal economy in the hospitality sector. Municipal social services deliver free meals to her door because she typically has little left for food after contributing to communal maintenance costs for her apartment block, and paying for utilities and medication.

Ildikó has type-2 diabetes and high blood pressure. Her doctor has told her she should measure her blood sugar three times a day, which requires a single-use blood glucose test strip each time. A pack of six paper strips costs 4,000 HUF (€10), and the monthly cost of following her doctor’s instructions would be 60,000 HUF (€151), effectively using most of her pension. She said:

I can’t afford to measure my blood sugar. Who will pay for it? When I requested a medical subsidy, it was refused. My last pension raise was 3,000 HUF (€8), which won’t even pay for one pack of the little paper slips for testing my blood sugar. I get free meals delivered to me, but I can’t afford to maintain the diet I need to manage my diabetes. I don’t feel respected, and I don’t think the state is taking care of me. I have no hope for the future and will live like this until the end of my life.

Tibor, 67, from Budapest’s XVII district, tended livestock from age 15 on a state cooperative and then for a private company until the mid-1990s. He then worked in a factory. When he retired four years ago, he said he was told that only six years of his working life had counted as legal employment with pension contributions: he receives 42,000 HUF/month (€106). He has lived in a homeless shelter in Budapest for about 15 years and barely has enough money to buy food. “I have health problems with my arteries, dizziness, my ears are oozing, and the veins on my legs are very itchy, but poor people can’t buy medicine,” he said. “It is what it is.”

Hungary has a public means-tested support program, under which people on low incomes with serious chronic health conditions can apply for a card to meet certain healthcare costs, valid for a specified monthly amount of up to 12,000 HUF (€30). However, based on interviews, it was not clear that such support was adequate to prevent hardship associated with out-of-pocket healthcare costs or uniformly received by those who would benefit from it. Some older people interviewed were effectively denied their right to health because they could not afford prescribed medication and medical supplies.

International and Regional Human Rights and Social Rights Standards

Hungary is a party to the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights which obligates it to fulfill the right to social security. The UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, which monitors the treaty’s implementation, has provided authoritative guidance on what that obligation entails, including in relation to minimum protections and adequacy of benefits over time. The committee’s guidance includes a requirement to address structural problems with social security system design, including pension coverage for workers in the informal economy and gender gaps.

States parties to the covenant must also fulfill the right to an adequate standard of living, which includes “adequate food, clothing, housing, and the continuous improvement of living conditions” and the right to health.

Despite being party to the treaty, Hungary has not reported to the committee in more than 10 years, limiting monitoring of its compliance.

As a European Union member state, Hungary is also bound by the union’s Charter of Fundamental Rights, which in article 34 includes obligations to protect entitlements to social security and social services, and to respect the right to social assistance to combat social exclusion and poverty.

The right to social security is also contained in the International Labour Organization’s Convention 102 and the European Code of Social Security (original and revised). However, Hungary has not ratified these instruments.

The (Revised) European Social Charter includes “the right of elderly persons to social security” (article 23), which is understood to include pension and benefit levels sufficient to “lead a decent life” and play an active part in public, social and cultural life. The Charter further contains “a right to protection from poverty and social exclusion” (article 30).

However, Hungary has not accepted either of these provisions, meaning that people in Hungary have no means by which to hold the government to account. In the last available examination of Hungary in 2021, the European Committee of Social Rights, which supervises compliance with the Charter, found that the minimum pension in Hungary was “manifestly inadequate.”

The European Committee of Social Rights has developed recent jurisprudence setting out that in order for people to enjoy their rights to housing and health under the European Social Charter, for example, they must have “stable, consistent, and safe access to adequate energy.” The Committee has also set out guidance to state parties noting the importance of addressing structural shortcomings in social security systems which exacerbate the effect of cost-of-living crises.